Tags

Picture the scene: outside a well-known Dublin pub, in the middle of town, on a Good Friday morning (or afternoon or evening). But the doors are shut, not a sign of life, and a radio reporter or TV crew is about to pounce…

Their prey is the next gaggle of bewildered tourists who’ve arrived in town in search of the “famous Irish crack” at Easter, only to find all the pubs are shut.

(In the business this annual media feeding frenzy is known as “An In-Depth Vox Pop”. It might even end up as the “And Finally…” bit on the six o’clock news.)

These tourists have just discovered that, in Ireland, Good Friday is the one day of the year – besides Christmas Day – when all the pubs across the land are closed. Or if they do open, it’s only to serve food and soft drinks (strictly no gargle).

The law concerned, the Intoxicating Liquor Act of 2000, updates a 1927 ban on the sale of alcohol, or “to open or keep open any premises for the sale of intoxicating liquor, or to permit any intoxicating liquor to be consumed on licensed premises” on these two particular days of the year.

Just as scientists are able to detect the faint echoes of the Big Bang from that Thursday teatime 13.8 billion years ago (approx), even today you can still feel the final tremors and vestiges of The Bad Old Days, when Ireland was a Catholic fundamentalist State, with its Magdalene laundries and industrial schools, and its draconian censorship of artists, and Archbishop McQuaid lecturing the nation about the fires of hell and eternal damnation.

Today, despite all the talk of a new multicultural post-Riverdance Ireland, of a land fit for people of all religions and none, the Angelus bells still chime at midday on the State’s main radio station and at 6 pm on RTÉ 1 TV, our Constitution still begins “In the Name of the Most Holy Trinity…”, our judges must swear an oath saying they are Christians, and there’s still a ban on drink on Good Friday.

So this ban is a hangover (wrong word?) from the dark ages when Church and State were in bed together, with the Church very firmly on top. Try telling that to the tourists gagging for a pint.

Some publicans don’t mind the Good Friday ban – their bars and off-licences will do a roaring trade on the eve of it anyway, and Good Friday is the one day of the year when they can close the doors and do up the floors and walls. Their staff get a welcome day off too.

But the Licensed Vintners’ Association, using the slogan #abouttime (not the most unique of hashtags, is it?), has been campaigning for an end to the ban. Or as its chief executive Donall O’Keeffe puts it:

This year there was a particular urgency around this issue, given the Ireland 2016 celebrations would focus on the Easter weekend and that we have an international soccer friendly between Ireland and Switzerland taking place in the Aviva Stadium on Good Friday itself.

Catholic Ireland is dead and gone but…

Yet alongside St Patrick’s Day and Leaving Cert Results Day, Good Friday has evolved into one of the booziest days of the year.

It all starts on the evening before, on Holy Thursday, aka Happy Off Licence Appreciation Day, with sheer mayhem in the off-licences and supermarket drinks aisles, as citizens stock up for a twenty-four-hour siege. The outside observer might think a permanent prohibition was about to come into force or, at the very least, the world was coming to an end.

As for the pubs, the Irish are renowned for walking on water and hopping across hot coals to perform an ancient ritual called Getting The Last Shout In (when last orders are called). Multiply that a hundredfold to get an idea of what the rush is like on Holy Thursday night.

The ban has become an excuse for locals to have the biggest pagan party of the year. Good Friday is National Designated House Party / Barbeque / Whatever Day. Everyone gets slabs of tinnies and lashings of wine from the offy on the Thursday night and holds a massive party the next day.

The exemptions

A collective moan goes up each year about this archaic legislation. But it is also accompanied by intense discussions about ingenious ways to circumvent the ban.

How a private “Club Gathering” would surely qualify for a licence, right?

Or how the Kennel Club holds its dog show at the RDS in Dublin on Good Friday, doesn’t it?

Or how the greyhound racing in Harold’s Cross and Shelbourne Park is exempt, surely? (All this leading to a sudden outbreak of very thirsty dog-lovers.)

Or how, instead, you might take a shining to the arts. “Let’s go to the theatre, the play’s shite or so I’m told but sure you can always get a feed of pints in the interval.” (Actually drinks in a theatre are no longer exempt, AFAIK).

Or how you could always book a hotel room and order room service or decamp to the Residents’ Bar. Or go on a booze cruise outside the territorial limits of Irish waters and see the sunny delights of, er, Holyhead.

Or how you just need to produce a valid travel ticket to get served in the bar of the airport or train station (and when on board the plane or train).

Or simply go to a restaurant. The law says that alcohol can be “ordered by or on behalf of that person at the same time as a substantial meal is so ordered” in a restaurant or hotel, as long as it’s “consumed by that person during the meal or after the meal has ended”.

But that’s in a restaurant. Not in a gastropub. And not for the subsequent ten hours after you’ve finished your grub.

The bona fides

During the era of the horse and bicycle, you would be exempt from the licensing restrictions of “normal” drinking time if you were a “bona fide” traveller.

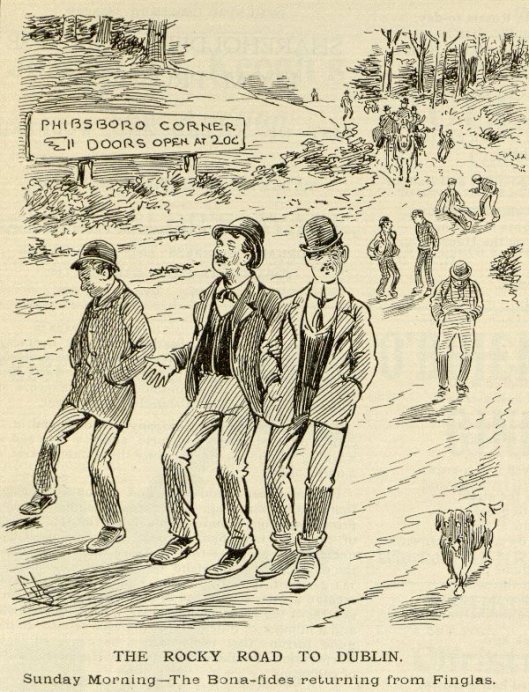

As closing time approached, hordes of punters from the city pubs would descend upon the countryside, propelled by bicycles or the internal combustion engine, in search of a suitable “bona fide” establishment outside the city limits.

“Bona fides” even became a noun for this subspecies. As in, “Arra go on and gis a pint so, we’re the bona fides.”

How the Lepracaun Cartoon Monthly portrayed the bona fides in 1905

As Flann O’Brien explains in “Drink and Time in Dublin”:

The theory is that all travellers still proceed by stage-coach and that those who travel outside become blue with cold after five miles and must be thawed out with hot rum at the first hostelry they encounter, by night or day.

After the bona fide pubs, there were always the “kips” – after-hours drinking dens or speakeasies of which two of the most famous Dublin ones were run by the Fawcett family from the 1930s to mid-1960s: the Cafe Continental at 1a Bolton Street near the corner of Capel Street, and the Cozy Kitchen on nearby North King Street.

The holy hour

Then there was the “holy hour”, in which pubs had to close from 2.30 to 3.30 pm each day. Despite the name, it had nothing directly to do with religion this time, though it came from an era when the actual devotional holy hour was still an everyday feature in Catholic life.

The holy hour closure rule was abolished in 1988, along with the associated practice where customers would attempt by various ingenious means to be “locked in”, i.e. hidden away in a snug at the back of the pub, in said “lock in” until the holy hour was over, or closing time was long past, or Good Friday had been and gone for another year.

All three photos of pubs here are of “Bongo” Ryan’s in Parkgate Street, Dublin. Its seafood chowder (also pictured above) is to die for.

Pingback: Flann O’Brien and a wheel revolution | Mel Healy

Seems 2017 will be the last year of the Good Friday alcohol sales ban here. Last week the Government said it would not oppose a Bill in the Seanad calling for the restriction to be abolished. The change is likely to come into effect for Good Friday 2018.

For this final year though, Publin.ie has some up-to-date tips on where to get the gargle:

http://publin.ie/2017/7-ways-to-get-a-drink-on-good-friday/

Addendum: yesterday’s Good Friday was the first one that pubs were allowed to open, after the 91-year-old ban was lifted.